Natural Materials

Behind the success of stone carving in Cambodia is the stone itself. The most popular stone used for carving is 400-million-year-old sandstone found in Banteay Meanchey, as well as Kompong Thom and Pursat. This type of stone is perfect for carving and has been used for all kinds of sculptures ranging from simple little stone sculptures to giant Buddhas.

Stone from Phnom Kulen is used for some of the more elaborate carvings, such as the temple carvings at Angkor Wat, but the Cambodian government has restricted usage of this stone for restoration purposes only.

The Beginnings of Khmer Stone Sculpture

The art of stone carving in Cambodia has roots that predate the foundation of the Angkor kingdom by many centuries. Some of Cambodia's oldest known stone sculptures were made in the Funan kingdom (located in the modern-day south of the country), which existed in the 1st or 2nd century AD until the 6th century AD, as well as in the pre-Angkor kingdom of Chenla.

During this period of time, Cambodia was exposed to a heavy amount of Indian culture due to the opening of trade routes between the Middle East and China which passed through the kingdom. This influence came primarily in the Sanskrit language, which was used in inscriptions, and in the Hindu and Buddhist faiths.

Hinduism became Cambodia's official religion during this period of time and remained the official religion until the 12th century AD. Many of the sculptures from this period of time were made of the three principal deities in the Hindu religion. That is, Brahma (the creator), Shiva (the destroyer), and Vishnu (the preserver).

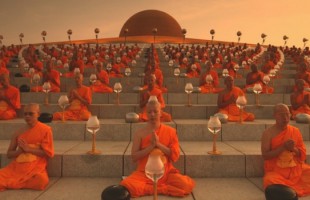

Buddhism was introduced sometime in the 1st century AD and gradually flourished in the Cambodian kingdoms along with Hinduism. Sculptors were carving sculptures of the Buddha and the Bodhisattva some 500 years later.

Both Hindu and Buddhist-themed sculptures from this period of time had a strong Indian influence in their delicately-carved and detailed body features, a princely disposition that still manages to remain benevolent, and body postures that feature a slight hip sway. Also, both Hindu and Buddhist sculptures were placed around temples and were often created for this purpose.

A new and unique Khmer style of sculpture began to appear in the 7th century AD. This style was more frontal in nature, extremely accurate and life-like in details, and often featured a prominent, amiable smile (i.e. the smiling Buddha statues from the period).

Stone Carvings and Sculptures of the Early Angkor Period

The Angkor period began in 802 AD when Jayavarman II was proclaimed a "god-king" and "universal monarch", declared independence from Java, and proclaimed a unified Khmer kingdom.

The massive stone sculptures became popular during the reign of Indravarman I, one of Jayavarman II's successors, who ruled from 877-886 AD. It was during his reign that the capital city of Hariharalaya (16 miles south of Angkor) was established and with it a number of temples in or around the city. These temples were - and still are - very luxurious and the sculptures of the period reflect the splendor of the era. The statues and sculptures are massive, imposing, and somber.

Statues from the early Angkor period were typically Hindu gods and goddesses such as Vishnu and Shiva built on a massive, grand scale.

The Glory and Splendor of Angkor

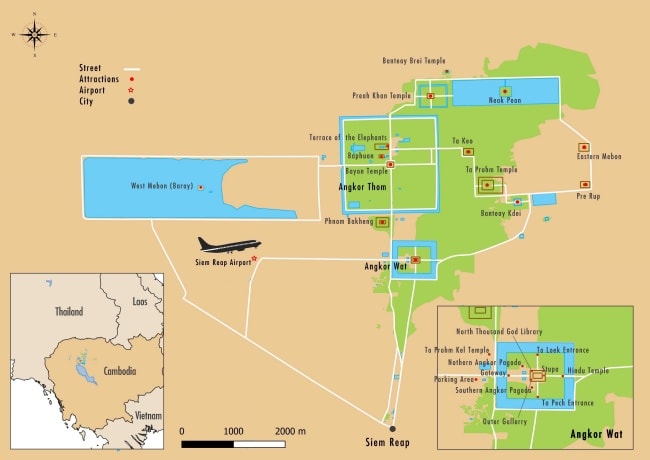

At the end of the ninth century AD, Indravarman's son Yasovarman I relocated the capital of the kingdom to Angkor. For most of the next 400 or so years, Angkor would remain the capital of the Kambujadesha (or Kambuja) kingdom and a vast number of temples, including the famed Angkor Wat, were built around the capital city.

Angkor Wat

Angkor Wat, one of the world's most magnificent religious sites and Cambodia's national treasure, was built in the 12th century AD during the reign of Suryavarman II (1113?-about 1145 AD). Angkor Wat features some of the most magnificent and famous stone carvings and murals found in Cambodia.

Built at first as a Hindu temple, Angkor Wat became a Buddhist temple over time. Statues of both Vishnu and the Buddha can be found across much of the temple complex. However, much of the temple's fame stems from the murals that can be found on the inner walls of the outer gallery. Intricately carved murals of scenes from the Hindu epics the Ramayana and the Mahabharata as well as of Suryavarman II can be found on these walls.

Here is everything about Angkor Wat

The Fall of Angkor

The Khmer empire fell in the year 1431 when Thai forces from the kingdom of Ayutthaya (modern-day Ayutthaya province, Thailand) launched a number of raids on Kambujadesha and eventually captured Angkor. The Khmer dynasty moved its seat of power south to Phnom Penh, which is now the capital of the modern-day Cambodian nation.

After the fall of Angkor and the Khmer empire, Khmer carving in general became limited to the handicraft-type projects we know today. That is, small Buddha sculptures and statues, deity carvings, and so on.

The Decline of Khmer Stone Carving

During the turbulent years of the war raging next door in South Vietnam, civil war, and totalitarian rule by the Khmer Rouge, the art of stone carving in Cambodia was almost completely lost. Many of the country's artists were either killed in war or murdered by the Khmer Rouge during the period of their rule from 1975-1979. A few artists managed to flee abroad and some of these artists have returned home to help teach the precious traditional arts to a whole new generation.

Stone Carving in Today's Cambodia

Since the 1980s a new generation of artists in Cambodia have begun learning the traditional arts and crafts of the country including stone carving and have kept those traditions alive.

During the 1980s and 1990s, a number of Cambodian art students went to various Communist bloc nations in eastern Europe such as Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, and the USSR to learn the art of stone carving. These art students are today's artists and teachers in Cambodia.

In addition, a number of foreign and domestic NGOs and art organizations have been set up in or have gone to Cambodia to teach the arts, preserve the existing historical pieces, restore the decaying ancient temples, and help Cambodian artists turn their passion for art into businesses. One of the most prominent of these groups is Artisans d' Angkor, which was set up by the Cambodian government organization Chantiers-Écoles de Formation Professionelle (CEFP). Not only has this group done all of the above but has set up a number of shops around Cambodia where their students can sell their crafts! Some of their shops can be found in Phnom Penh (both in the city and at the airport) and in Siem Reap, near Angkor.

05/03/2026

05/03/2026

Jolie LIEMMy name is Jolie, I am a Vietnamese girl growing up in the countryside of Hai Duong, northern Vietnam. Since a little girl, I was always dreaming of exploring the far-away lands, the unseen beauty spots of the world. My dream has been growing bigger and bigger day after day, and I do not miss a chance to make it real. After graduating from the univesity of language in Hanoi, I started the exploration with a travel agency and learning more about travel, especially responsible travel. I love experiencing the different cultures of the different lands and sharing my dream with the whole world. Hope that you love it too!